Many Kansas cattle operations rely on some type of harvested feed to use in the winter months, and common among those sources are forage sorghum, millets, sorghum-sudangrass, and sudan. Forages in the sorghum family are prone to two different problems when feeding cattle: nitrate poisoning and prussic acid (hydrocyanic acid, HCN) poisoning. Millet (proso and pearl) do not contain prussic acid but can have nitrates. Prussic acid and nitrate poisoning are easy to confuse because both result in a lack of oxygen availability to the animal and are more likely to occur when the plant is stressed (fertility, hail, drought).

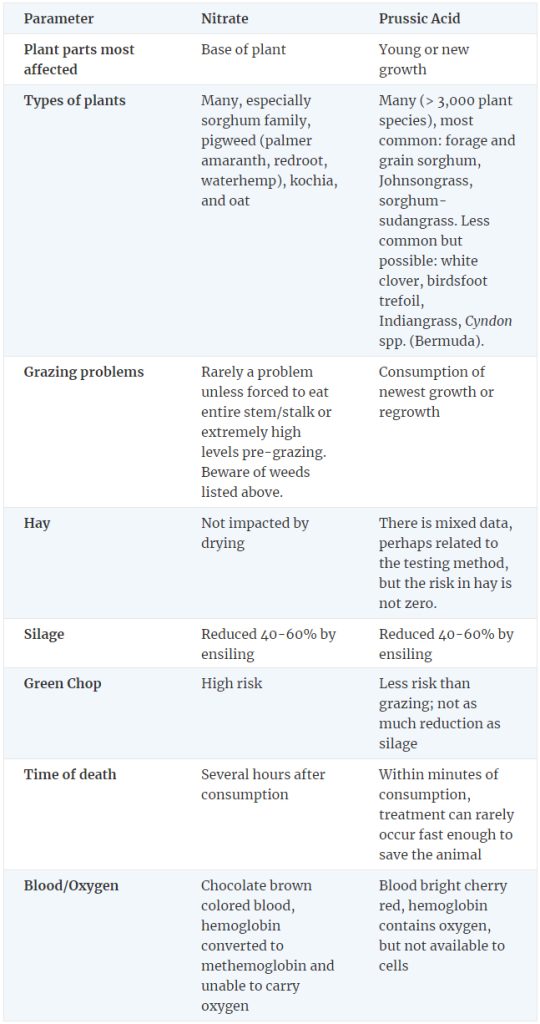

Table 1. Key characteristics of nitrate and prussic acid poisoning.

In dry areas of the state, cattle may be removed from pasture early. Bringing hungry cattle into pens with weeds can be very dangerous as the nitrate concentration may be elevated throughout the plant and animal intake high. Manure in corrals can contribute to the elevation of nitrates in the weeds. Elevated nitrates may not result in death but could cause abortions. Be careful never to turn hungry cattle onto weeds, minimize consumption of weeds in corrals, and have other safe feed to consume besides weeds to reduce risk.

Prussic acid concentrations are greater in fresh forage than in silage or hay because HCN is volatile and dissipates as the forage dries or ensiles. Additionally, hay or silage that likely contained high cyanide concentrations at harvest should be analyzed before it is fed. This second statement is often forgotten, and it’s assumed that when the plant dries, all the cells are ruptured and any HCN is released. To confirm this, we measured dhurrin content in sorghum hay. The dhurrin content was stable from 1 week to 2 months of dry storage. In the plant, dhurrin (the precursor to HCN in sorghum species) and the enzyme that converts it to cyanide are stored in separate compartments within the cell. The compartments are ruptured when the plant is eaten, and the cyanide is formed and released. While the enzyme that converts dhurrin to cyanide is inactivated with drying, rumen enzymes can make the same conversion after consumption. If hay is made from forages in the sorghum family or other susceptible species, testing for prussic acid in forage that has suffered from drought, hail, or fertility issues is advised. The frequency of issues with prussic acid in harvested forages may be relatively low; however, testing is cheap compared to the cost of losing even one animal.

Management recommendations common to both prussic acid and nitrates include:

- Test first, don’t gamble. Keep in mind that different labs use different tests that have different scales.

- Feed animals with a known safe feedstuff(s) and have them full before introduction to potentially problematic feeds. Don’t turn in hungry.

- Ensiling will reduce concentrations of either by 40-60% in well-made silage, but silage put up under less-than-optimal conditions could still contain very high levels. If extremely high before ensiling, a 50% reduction may not be enough to result in safe feed. Test ensiled feed before feeding.

- Dhurrin concentrates in the newest growth and regrowth of the plant and with more plant growth (>24”), concentration levels may be diluted if measuring the whole plant.

- Nitrate concentrates in the base of the plant and is least in head and leaves, grazing or cutting high can reduce nitrate levels in the forage.

- Do not harvest drought stressed forage within 7 to 14 days after good rainfall to reduce the levels of accumulated nitrates.

If testing before grazing, samples should reflect what the animals are expected to consume, generally leaves and upper portion of the plant. Sample a minimum of 15 sites across a given field. One method is to sample from each corner and the center by walking diagonal lines and sample plants every 50-100 steps or as appropriate for field size.

We expect levels of nitrates and prussic acid to be variable across a field, so more samples are better than less. A rule of thumb is to sample 10 to 20% of the bales per field or cutting as a minimum. Be aware of areas of the field that exhibited more plant stress than others. If large enough areas, you may want to sample them separately. Your acreage size and feeding methods likely factor into this decision. Use a forage probe that cuts across all plant parts in a bale rather than a grab sample from individual bales or windrows. Most county extension offices can help with sampling procedures and equipment.

Prussic acid in sorghum following a freeze event

Frost causes plant cells to rupture and prussic acid gas forms in the process. Because the prussic acid is in a gaseous state, it will gradually dissipate as the frosted/frozen tissues dry. Thus, risks are highest when grazing frosted sorghums and sudangrasses that are still green. New growth of sorghum species following frost can be dangerously high in prussic acid due to its young stage of growth. It is recommended to wait ten days until after a killing freeze before grazing. Sorghum and sudangrass forage that has undergone silage fermentation is generally safe to feed.

For more complete information on these problems, see these publications: Nitrate Toxicity, Prussic Acid Poisoning, and Managing the Prussic Acid Hazard in Sorghum. If you have samples with high prussic acid concentrations and are willing to share information on variety, growth, fertility, and harvest conditions, it will be helpful as we strive to understand this issue better.

Sandy Johnson, Extension Beef Specialist, Northwest Research-Extension Center

sandyj@ksu.edu

John Holman, Cropping Systems Agronomist, Southwest Research-Extension Center

jholman@ksu.edu

Augustine Obour, Soil Scientist, Agricultural Research Center – Hays

aobour@ksu.edu

Logan Simon, Area Agronomist – Southwest Research-Extension Center

lsimon@ksu.edu