By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

(Second in a series)

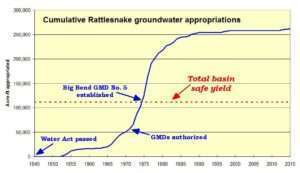

By the time a stream gauge was built in 1973 to measure the amount of water reaching Quivira National Wildlife Refuge, the area’s groundwater was likely over-appropriated. Proving it was unlikely.

At that time a water right was not required to start irrigating. A water right was defensive, a shield that prevented others, now or later, from “impairing” that right.

The gauge is in northeast Stafford County near the town of Zenith, which at the time still had a post office (it closed the following year), and just two miles from the west edge of the Refuge. The Refuge, owned and operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, had filed for a water right in 1957 for more than 14,000 acre-feet of water (one acre-foot is about a third of a million gallons). The gauge would record how much water reached the Refuge.

In January this year, the Fish and Wildlife Service became a defendant in a federal lawsuit filed by Audubon of Kansas that accuses the agency of failing to protect its own water right.

An investigation by the Kansas Division of Water Resources in 2016 concluded that upstream pumping by users with junior water rights – rights requested after the date in 1957 when the Service filed its request – had regularly and substantially impaired Quivira’s water right.

By 2007, users with junior rights were reducing streamflow by 30,000 to 60,000 acre-feet each year, the investigation said.

Not everyone with a water right was convinced.

“[Irrigators] keep saying they don’t have a problem because the water levels aren’t changing,” says David Barfield, who until this past October was chief engineer for the Division of Water Resources. Under state law, the chief engineer is responsible for enforcing water regulations.

Streams essentially are overflows for aquifers underground. As aquifers are filled – or recharged – by water that seeps into the soil, the excess leaks up, creating streams and rivers. The rate at which that happens varies wildly with geology and topography. If the water table drops, by drought or pumping, streamflow declines.

“We do recharge at a very high rate,” says Orrin Feril, manager of the Big Bend Groundwater Management District 5. All but the western-most tip of the Rattlesnake basin lies in the management district. “Because we are a sustainable aquifer we do not see the declines in the aquifer annually as we do in other parts of the state.”

Imbalance between inflow and outflow makes the water table rise or fall.

“The western half of our district does have declines,” he says. “Overall the Rattlesnake Creek watershed does not show those declines from pre-development.” Pre-development is considered to have ended around 1950 when center pivot irrigation caught hold in Kansas.

Data from the Kansas Geologic Survey compare the depth of water pre-development with levels in 2018; the water table in some parts of the watershed is higher now than it was 70 years ago, but on average it has fallen about 8 feet – a loss of about 1.4 million acre-feet of water.

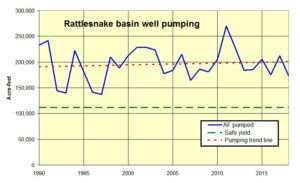

Whether that is viewed as substantial, reports show that the amount of water pumped is often twice the estimated recharge.

According to recharge maps developed by the U.S. and Kansas geologic surveys, annual recharge in the Rattlesnake basin is 112,000 acre-feet. Annual reports show that in the past 30 years, pumping in the basin has ranged from 137,000 acre-feet to 270,000 acre-feet.

And in spite of efforts that began in the early 1990s to restore streamflow on the Rattlesnake, the trend in annual basin pumping is up slightly.

Feril insists use and recharge are in balance.

“I have a hard time when people say we are unsustainable and drastic measures need to be taken,” he says. “I would like to see data that shows that, because if it’s true we need to be making some changes.”

The dispute over streamflow took a new turn in 2013 when Quivira National Wildlife Refuge lodged a formal complaint that asked the state to determine whether users with junior water rights were responsible for choking the flow into the refuge.

Barfield’s office released a report in 2016 confirming the impairment. Attention then focused on how to ensure adequate flow to Quivira.

The groundwater district wanted to provide Quivira with water from other wells to augment the Rattlesnake streamflow, Barfield said. The state said that wasn’t enough.

“We had a longstanding dispute that really hasn’t been resolved yet,” Barfield says.

By 2019, negotiations had stalled. Barfield announced he was preparing to order cutbacks in pumping, beginning in 2020. That’s when Sen. Jerry Moran’s office stepped in. Within weeks Quivira had withdrawn its request to secure its water right and declared a willingness to talk further with the groundwater district.

In July 2020, Quivira and the groundwater district agreed to a plan. The district would establish the ability to pump 11,000 acre-feet of water annually into the Rattlesnake upstream of Quivira, with the promise to add 6 acre-feet per day at critical times. In addition, it would attempt to retire 2,500 acre-feet of water rights from areas close to the stream; if that doesn’t happen, the District will try to have irrigators remove end guns from their center pivots.

“We believe we have a solution that will work,” Feril says.

Barfield doesn’t. He notes that when Sen. Moran met with users in St. John he essentially told them they need to find a long-term solution.

“I don’t know that he said, ‘The chief engineer is right,’ I doubt he said those words,” Barfield says. “But he basically said ‘This problem is not going to go away. You need to deal with it.’”

Barfield said he understands how difficult it is to weigh the immediate economic impact of cutbacks with the long-term benefits of preserving the aquifer.

“Those people are experts in delay,” he says. “The problem has to be remedied and augmentation is one way to reduce the impact … but our belief, based on looking at a lot of the science, is they really need to do reductions with augmentation.

“This is not over, by any means.”

One thing missing in the story from the time of the orginal stream flow until now how many trees have shown up within 100 yards of the creek? The creek that flows through my pasture in the 50s flowed year round now it’s dry almost every summer. No irrigation close but in the fall when the trees loose their leaves it starts again. Does the rattlesnake pick up flow in the fall?