Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

(First in a series)

(First in a series)

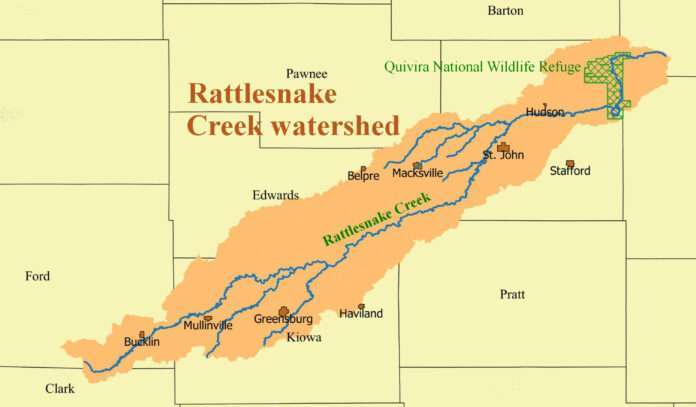

For decades Rattlesnake Creek, which supplies water to Quivira National Wildlife Refuge, has dwindled.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service tried everything. It complained. It formed an alliance with state regulators, the groundwater management district, local irrigators. Massive computer models juggled millions of pieces of data to understand surface-to-groundwater interactions. A 12-year plan was attempted to bring the water back.

But stream flow kept dropping in spite of increasing rainfall. A goal for pumping reduction was only 10 percent realized.

Finally, in April 2013, Fish and Wildlife formally asked state regulators to determine whether irrigation wells in the Rattlesnake Creek watershed were using so much water that not enough remained for Quivira, a 22,000- acre refuge within the Central Flyway. The refuge, in far northeast Stafford County, is a rare combination of inland salt marsh and prairie vital to hundreds of thousands of birds annually.

Three years later, the state had an answer from David Barfield, chief engineer in the Kansas Department of Agriculture, who holds the authority and obligation to protect water rights. The answer was unambiguous.

“The Refuge’s water supply has been regularly and substantially impacted” by upstream pumping, the report stated. Nearly all the pumping was by users whose water rights are said to be junior to the refuge’s. That is, their rights were granted after the refuge claimed its right. Under Kansas law, when there’s not enough water to go around, senior rights are satisfied first.

“The first in time is the first in right,” as KSA 82s-707(c) puts it. Quivira’s right is 77th of 2,586 in the watershed.

At this point, Fish and Wildlife was cleared to ask the chief engineer to “secure” its water – essentially to order upstream users with junior rights to reduce pumping enough to restore streamflow. However, Groundwater Management District No. 5 proposed a solution that included augmentation – pumping water from another source into the Rattlesnake. Here is the way Barfield summed up the situation in late 2016:

“On Thursday, December 1, we received the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s response to GMD #5’s Stakeholder Proposal of September 8,” Barfield wrote in a letter to the Groundwater Management District 5 board. “As you know, the Service declined the Basin’s offer principally on the grounds that it is insufficient in quantity and that placing augmentation infrastructure on the refuge as described in the offer poses ‘significant legal obstacles.’ It appears from its response that the Service intends to file a request to secure water, which we anticipate receiving soon. Nevertheless, the Service goes on to state that, ‘We look forward to continuing to work with GMD #5 as we seek a resolution to the matter that is fully protective of the interests of the United States.’”

While state law is clear that the chief engineer must prevent users with junior rights from impairing those with senior rights, regulations also say that if the users are in a groundwater management district, “the chief engineer shall allow the GMD board to recommend how to regulate the impairing water rights.”

That had already been done but Barfield gave GMD5 another shot, explaining that he wanted the parties to work together.

“We continue to hold that locally developed solutions are best,” he wrote. “For this reason, we request the basin stakeholders develop a revised settlement offer by February 15, 2017. He encouraged Fish and Wildlife to work with the groundwater district and allow basin stakeholders to negotiate a settlement.

If there is no settlement, he said, “… we will be obligated to develop an administrative remedy for implementation in 2018 and beyond.”

The groundwater district alternative was to create a Local Enhanced Management Area (LEMA), a tool that outlines goals for limiting water use in a certain area. The chief engineer must find that the plan should achieve the necessary reductions and comply with state law.

A year later there was no plan.

Fish and Wildlife filed another request to secure water.

“The Service appreciates being informed of any developments regarding the [LEMA] that is being drafted to remedy impairment,” it added dryly in a letter dated Dec. 13, 2018.

Two months later, in February 2019, Groundwater District 5 had completed its LEMA plan. Another non-starter. The chief engineer’s letter in July 2019 hints at some of the back-and-forth that accompanied it.

“In addition to several face-to-face conversations, a complete review of the technical and legal problems with the proposed LEMA was provided to you on May 30, 2019, via email,” Barfield wrote. “Since that review, my position on the acceptability of the proposed LEMA remains unchanged and you may consider this letter formal notification that LEMA proceedings will not be initiated to consider your current plan.”

The letter goes on to acknowledge a request two weeks earlier asking for yet another explanation of what elements an acceptable LEMA plan would need to include. Barfield reminded the District that outlines of acceptable elements had been repeatedly provided in the past. He noted letters, emails and informal reviews dating to an April 2018 letter from former Secretary of Agriculture Jackie McClaskey and other officials.

Then he delivered the bad news.

“As matters currently stand, I can no longer delay action in the basin,” Barfield wrote. “It is now necessary for me to exercise my duties as Chief Engineer and take action to protect the senior water right owned by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Therefore, I intend to directly administer the basin by administrative orders issued on or around September 1, 2019, and to become effective on January 1, 2020. Our intention is to provide time for local irrigators to plan for the 2020 growing season.”

Three months later, US Fish and Wildlife announced it was no longer asking that its water right be secured.

A lawsuit filed in federal court in January 2021 suggests one reason for the abrupt about-face. The case was brought by Audubon of Kansas and names the Department of Interior, USFWS, the Kansas Department of Agriculture and the Kansas Water Office as defendants, accusing them of failing to protect the refuge.

“During the summer and fall of 2019, Senator Roger Marshall, then serving as United States Representative for Kansas’s First Congressional District, sought and obtained repeated in-person and/or telephonic meetings with (Kansas) secretary [of Agriculture] Beam, in which Representative Marshall emphasized his desire that the junior water rights that were impairing the Refuge Water Right not be administered, despite the chief engineer’s clear and non-discretionary duty to do so,” the complaint alleges.

“During the Fall of 2019, United States Senator Jerry Moran sought and obtained in-person and/or telephonic meetings with [USFWS] Director Skipwith and secretary Beam, in which Senator Moran likewise emphasized his desire that the junior water rights that were impairing the Refuge Water Right not be administered, despite the chief engineer’s clear and non-discretionary duty to do so. “In October, 2019, Senator Moran and Director Skipwith, neither of whom has jurisdiction over the administration of water rights in Kansas, announced a bargain: The Service would withdraw its request to secure water for the Refuge Water Right, in exchange for GMD5 and KDA-DWR working together to find an adequate solution to the Refuge’s water-shortage problem by 2020.”

The defendants have until March 15 to respond.

(Next Week: Can the Rattlesnake be restored without cutbacks in pumping?)

Duane Schrag can be contacted at schrag.duane@gmail.com

Moran and Marshall respond

Sens. Jerry Moran and Roger Marshall declined to be interviewed for this story, but instead requested written questions. Moran followed form; Marshall issued a statement. Here are their replies:

From Sen. Jerry Moran:

Q. Please share how you became involved in the Rattlesnake Creek impairment issue, and what role you played in the decision by USFWS to withdraw its request to secure water.

A. I raised concerns regarding the water rights dispute surrounding the Quivira National Wildlife Refuge with then FWS Director Aurelia Skipwith last October, and explained the need for farmers and ranchers to be able to utilize groundwater in the basin. I appreciate Director Skipwith coming to Kansas and working with local farmers and ranchers on this issue. It was important to me for a voluntary solution to be reached that meets the future water needs of both local agricultural producers and the wildlife refuge. The agreement that was reached was the breakthrough we needed.

Q. USFWS’s complaints that its water right was being impaired by those with junior rights were first voiced more than 30 years ago. It participated for many years in joint efforts that involved GMD5 and local operators to ensure it had enough water to satisfy its water right. Those efforts were largely unsuccessful. What is your understanding of why those failed?

For an agreement to be reached, both sides had to come to the table to discuss solutions that meet the future water needs of both local agricultural producers and the wildlife refuge. Currently, the USFWS and GMD5 are both working to fulfill their sides of the agreement, and I am hopeful we are on the path to long-term success for the refuge and the local farmers and ranchers.

Q. What solutions are possible that will allow Quivira NWR to exercise its water right?

When I shared the dispute regarding the water rights of the Quivira National Wildlife Refuge with Director Skipwith, I explained the need for farmers and ranchers to be able to utilize groundwater in the basin. The agreement reached works to meet the needs of both local agricultural producers and the wildlife refuge by augmenting the streamflow of Rattlesnake Creek and encouraging voluntary conservation efforts. Under the terms of the agreement GMD5 will construct a streamflow augmentation wellfield to help supply Rattlesnake Creek with groundwater.

This agreement aims to meet the future water needs of both agricultural producers and the refuge which provides important habitat for migratory birds and other species of wildlife. While working to resolve this dispute through non-regulatory measures benefits farmers and ranchers, it also supports the rural communities in central Kansas that depend on the agriculture industry.

From Sen. Roger Marshall:

I have owned property along the Rattlesnake Creek for nearly 30 years and spent countless hours removing invasive species from its banks and working to improve water flow downstream. I have also hunted birds and waterfowl at Quivira Wildlife Refuge for many years so understand the habitat needs of migratory birds in the region.

In 2019, when discussions between the Kansas Department of Agriculture’s Division of Water Resources and area property owners began to take shape, I heard from area farmers, ranchers and property owners who were concerned about the severe impacts KDA’s proposal to reduce water use would have on their productivity and farm income. Agriculture is the economic engine of this region of the state and reducing a farmer’s capacity to irrigate his or her field is both diminishing their productivity and their overall farm income. That decline would have ripple effects that would have been felt throughout the region.

I sat down with the state’s chief water engineer to better understand what was needed to resolve the situation and encouraged moderation in any changes to water usage for farmers in Groundwater Management District #5.

My office was also part of ongoing discussions with U.S. Fish and Wildlife staff, encouraging them to engage with local stakeholders and come to a resolution that did not substantially impact the agriculture industry.

I applauded USFWS’s decision in 2019 to not seek an impairment for the 2020 growing season and have continued to discuss the issue with members of the new Administration, including questioning Interior Secretary Nominee Rep. Deb Haaland about the issue during her confirmation hearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources.

I am passionate about preserving the refuge for future generations, but we cannot let outside advocacy groups substantially impact the resources and growing practices of our farmers and ranchers.

As a member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, I will prioritize continuing the discussions around this issue and work to find a solution that benefits all parties involved.

Complaint filed by Audubon of Kansas in its lawsuit

The final report released by the Kansas Division of Water Resources finding that upstream.