Last weekend’s heavy November snowfall may signal the approach of a particularly snowy winter for Kansas.

This is a year of El Niño, a climate pattern that historically results in Kansas seeing more precipitation than usual, assistant state climatologist Matthew Sittel noted in a report published Nov. 16.

Nine days later, on Nov. 25, Topeka saw its heaviest November snowfall in 135 years, with 6.3 inches falling that day, followed by 0.9 inches more the following day. Parts of Kansas saw 12 inches of snowfall or more, according to the National Weather Service.

What does the National Weather Service say?

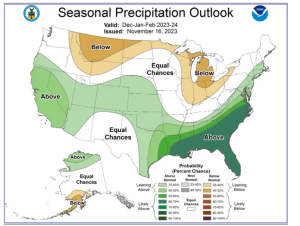

More than 90% of the area of the state of Kansas is likely to see above-average precipitation over the months of December, January and February, the National Weather Service said in a graphic posted recently on its website.

A small sliver of northeast and east-central Kansas, along the state’s border with Missouri, is expected to see equal chances of above-average or below-average precipitation, that site said.

‘Meteorological Superhero’

Sittel’s report said a snowier-than-usual winter in this drought-stricken state will become even more likely if the current El Niño becomes a “Super El Niño,” which the National Center for Atmospheric Research has predicted will happen.

The “Super El Niño” name “conjures up images of a meteorological superhero,” Sittel’s report said. “As it turns out, a Super El Niño could be a hero for Kansans.”

What is El Niño?

Last June brought the start of the current El Niño, a warming of surface waters in the Pacific Ocean. In a departure from normal, Kansas has seen below-average precipitation in the months since.

El Niño’s Spanish-language name refers to the baby Jesus and was given by South American fishermen who noted that some years, around Christmas, the waters off their Pacific coast would mysteriously become warmer.

El Niño typically starts with a slackening of trade winds that blow west across the Pacific at the equator, weather experts say. The winds provide constant pressure that keeps the ocean slightly higher on its Asian side.

As they ease up, massive amounts of heated tropical water slosh from one side of the Pacific to the other.

Water and air temperatures rise across millions of square miles in a long, relatively narrow equatorial zone between Indonesia and South America. Water expands as it heats up, meaning warmer seas become higher seas.

Heat energy consequently creates an imbalance in surface air pressure that affects weather patterns throughout the world, bringing record high temperatures in some areas and storms and flooding in others.

How has El Niño historically affected Kansas?

In Kansas, El Niño has historically brought above-average rainfall and snowfall, Sittel’s report said.

Kansas has seen 73 winters since 1950, with 21 coming during an El Niño, it said.

Nineteen winters came during a La Niña — El Niño’s counterpart, in which surface temperatures are below normal in the area of the Pacific that El Niño affects — while 33 have come at times when neither is taking place, the report said.

On average, it said, Kansas sees 2.72 inches of precipitation over the months of December, January and February during El Niño winters; 2.48 inches during La Niña winters; and 2.34 inches during neutral winters.

Precipitation and snowfall amounts are not the same. Snowfall totals are reported as the amount of liquid water the snow produces upon melting, said the website of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“An old rule of thumb was that for every 10 inches of snow, there would be 1 inch of water (10:1),” says the website for the National Weather service office in La Crosse, Wisconsin. “However, this is far from the norm, and recent studies indicate that a 12:1 ratio might be more representative (on average) for the Upper Midwest.”

Using the figure of 1 inch of precipitation for every 10 to 12 inches of snow, the extra 0.38 inches of precipitation Kansas sees on average in El Niño winters would equate to between 3.8 inches and 4.56 inches of additional snow.

What is a ‘Super El Niño?’

This year’s El Niño is shaping up to be stronger than most, Sittel stressed in his report.

“It does appear that the stronger the El Niño event, the more precipitation Kansas gets on average,” he wrote.

Sittel noted that the National Center for Atmospheric Research predicted Sept. 26 that December would bring a “Super El Niño.”

A Super El Niño occurs when water temperatures reach a point 2 degrees warmer than average in the area of the Pacific affected by an El Niño.

‘Reason to be optimistic’

The added precipitation brought by a Super El Niño would greatly benefit drought-stricken Kansas, Sittel said.

The Sunflower State since 1950 has experienced five winters during Super El Niños, with those being in 1965-66, 1972-73, 1982-83, 1997-98 and 2015-16, Sittel’s report said.

It said average precipitation during those five winters was 3.49 inches, or 1.15 inches above the average of 2.34 inches recorded during neutral winters.

Using the figure of 1 inch of precipitation for every 10 to 12 inches of snow, the extra 1.15 inches of precipitation Kansas sees on average during Super El Niño winters equates to between 11.5 inches and 13.8 inches of additional snow.