As reported in High Plains Journal. From June 2020 through June 2021, Minnesota and Kansas had the second and third highest number, respectively, of farm bankruptcies in the United States, according to a recent report by the American Farm Bureau Federation.

Most farmers and ranchers don’t have to face the hardship of losing their farm, but financial pressures may still weigh on them, along with fluctuating crop and livestock markets, the pandemic, drought, politics and other stresses.

“Caring for your own health and wellness is often overlooked amid these many concerns that we juggle. This can take a toll on individuals and families and can lead to mental and emotional distress, substance abuse, anxiety, depression and even suicide,” said Kansas Deputy Secretary of Agriculture Kelsey Olson during a session on ag and rural stress at the virtual Kansas Governor’s Summit on Agricultural Growth, Aug. 26.

“I think that not all issues we face are mental health issues, but just about all the issues we face are stress—and the two of those contribute and feed on each other,” said Meg Moynihan, senior advisor on strategy and innovation, Minnesota Department of Agriculture. Moynihan presented the session “Supporting Farmers and Ranchers in Stress” at the ag summit.

She and her husband, Kevin Stuedemann, also own and operate Derrydale Farm, a 70-cow organic dairy in Le Sueur County, Minnesota.

Although she is not a mental health professional, she is a “linker and a networker” with personal experience dealing with farm stress, especially following the loss of milk markets in 2016. Moynihan works with a broad range of professionals whose work supports farmers and ranchers so that they can be better partners.

The stress onion

Moynihan uses an onion to illustrate her view of stress.

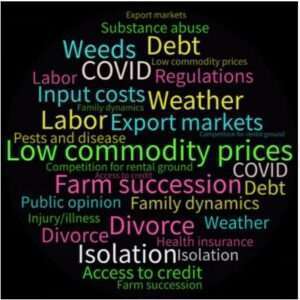

Moynihan said stresses farmers and ranchers face might be micro or macro and episodic or chronic.

“So many of these issues are outside of the direct control of the farmer or rancher.”

She said farmers and ranchers are proud of being self-reliant, strong and able to hold things together. They feel responsible not only for their farm but also for natural resources, their families, communities and kids.

“And at the same time, there are all of these issues that are floating past them that they feel the need to reach out and grab ahold of and manage, but they’re just too slippery,” Moynihan said, which can become overwhelming.

“The tension between feeling a sense of responsibility and feeling a lack of control has a great deal to do with farmers’ identity and how they see themselves.”

What makes farm stress different? One reason is that farmers usually work where they live and rarely have breaks from the work. Their coworkers are also family members, which can be a positive experience but may also cause more stress if there are conflicts.

Moynihan said that as the number of farmers continues to decline, the remaining ones experience the loss of community. “The loss of peers and increasing sense of isolation can be extremely draining,” she noted. “We used to have more people in the boat with us.”

Consumers’ fickle views toward farming also cause stress. Farmers are called the salt of the earth and the original small businesses, but they’re also blamed for climate change and accused of abusing livestock, she said. You never know whether the people you’re trying to feed love you or hate you.

Chronic stress may not be as noticeable as sudden, or emergent, stress, Moynihan said. Some of the signs that a farmer or rancher may be struggling are sleep disturbance, weight loss or gain, poor hygiene, gastrointestinal problems, irritability and withdrawal. These issues may lead to depression, anxiety, substance abuse, relationship problems and paralysis, or an inability to make decisions.

“Sleep is one of the first things to be disturbed when we’re upset,” she said, and asking someone about their sleep habits is one way to broach the topic if you’re concerned about how they’re coping with stress.

Help comes in many forms

“We don’t think it should be so hard to find help,” Moynihan said of her work with the state of Minnesota. “Help can be as close as the veterinarian who comes to do a preg check on your animals or the lady at the FSA counter. Everybody needs something different. Some people need their family doctor. Some people need a mental health provider if they’re struggling.”

Or they may need to find a different banker or speak to a lawyer or a pastor, she said. “We want all the people who interact with producers to be better grounded in recognizing and responding when they see farmers in trouble.”

Minnesota has invested in multiple resources so that individuals and communities can support one another. The state legislature approved funding for dedicated rural mental health specialists, who meet one on one to have conversations with farmers and ranchers in their homes or another location of their preference. There is no charge for the service to farmers and ranchers.

Minnesota also offers a helpline that can be called 24 hours a day. Text and email were recently added to accommodate all ages and technology levels.

Minnesota Farm Advocates help farmers navigate natural or economic disasters.

The Down on the Farm kit and workshop provide resources and training for those in agriculture-adjacent fields to offer support to farmers and ranchers.

The Red River Farm Network profiled farmers who went through a challenge and were willing to talk about it in short radio segments.

“When people hear from and about their peers, it’s really meaningful,” Moynihan said.

To address rural isolation, she also discussed the idea of forming “men’s sheds,” which began in Australia. The groups are self-directed and focus on doing things like volunteer work or other action-based projects. “They don’t talk face to face. They talk shoulder to shoulder,” she said. Those involved in the men’s sheds report decreased loneliness and isolation and increased health outcomes.

The topic of farm stress doesn’t belong to any one organization or effort, Moynihan concluded. Collaboration is the key.