A lack of child care options in rural Kansas leaves families desperate and threatens the future of small towns.

HAYS, Kansas — It started with a phone call late last month.

The child care that Zach and Aubrey Woolf had lined up for their 10-month-old daughter was closing, just a couple of weeks before Aubrey started back at her job with the local school district.

The news sent them scrambling.

They called over a dozen other child care providers in town and sent messages to 20 more. The Woolfs scoured a statewide database for options in their county. But there were exactly zero openings.

“There just seems to be a swarm of people all trying to find open spots for infants, and they’re few and far between,” Zach Woolf said. “There’s no hope.”

How dire is the situation in Hays? The Woolfs also posted their pleas to an active Facebook group dedicated to local parents searching for child care options. In this northwest Kansas town of about 21,000 people, that Facebook group has 1,400 members.

After several frantic days, the Woolfs found an opening for their daughter in a neighboring town 20 minutes away. It wasn’t ideal, but at least it was something.

Then, they got another phone call. That provider was injured in an accident and could no longer care for their daughter.

So, they crunched the numbers to see how it would affect their finances for Aubrey to quit her job.

“We were probably a week away from her talking to her advisor at the school and being like, ‘I can’t come because I have nowhere to send my child.’” Woolf said. “What are you supposed to do in that situation?”

It’s a dilemma families face across rural Kansas, where child care options are scarce and solutions to the chronic problem seem ever more elusive. For small towns desperate to attract new families and stop an exodus of young residents, solving the child care conundrum poses a matter of civic survival.

Wise investments

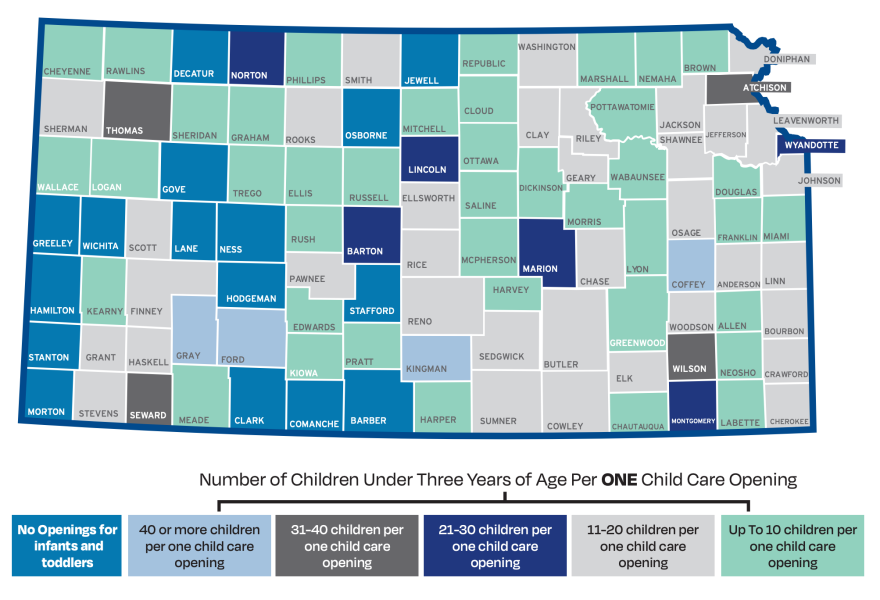

Child care scarcity squeezes communities statewide. In four-fifths of Kansas counties, more than 10 children compete for each open spot that can take a kid younger than three years old.

If finding child care is a stressful, competitive prospect in Kansas City and Wichita, that pales in comparison to family life in a county where you can count the number of day care options on one hand.

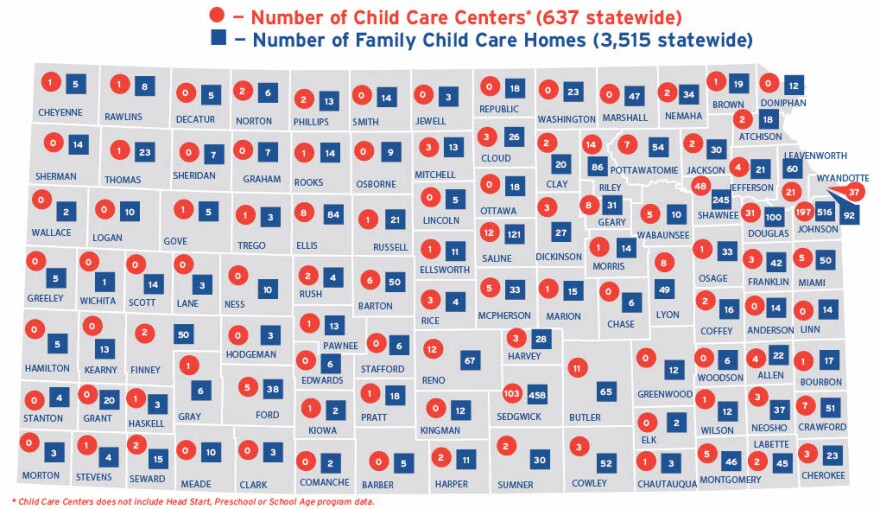

The Child Care Aware organization’s data shows 18 rural counties in Kansas have five or fewer child care providers. Wichita County in western Kansas has only one.

And that’s before any of those precious few providers close down.

More than half of Kansas counties have fewer child care options today than they had in 2019. Hays, for example, lost 16 providers over the past two years.

Bradford Wiles, associate professor and extension specialist in early childhood development at Kansas State University, said that small towns need to completely rethink the way they view child care.

“One of the things that rural areas really struggle the most with is recognizing child care as a utility,” he said, “as important to a rural community as electricity, as internet, as water.”

Wiles sees child care as an economic development issue.

If a town lacks options, families won’t move there or stay there. That means critical jobs go unfilled and the town’s tax base dwindles. And when families get distracted and stressed about their child’s care, that leads to less productivity on the job and taking more days off work to fill in the gaps.

It’s also an investment in the town’s next generation. When children get quality care, they’re more likely to have higher incomes and be healthy, productive members of the community as adults. Wiles said that for every dollar a town puts into early childhood development, it gets a return of $7 in the long run.

“It’s a no-brainer,” he said. “We have to see it as an investment in our population, in our families.”

But towns have to want to take action.

Wiles said effective solutions for this problem aren’t likely to come from the state level, but from communities coalescing around the issue — taking stock of their town’s specific needs, building a plan that fits those needs and dedicating public and private resources to implement the plan.

And for that to happen, he said community members need to realize that failing to invest in child care hurts them — even if they don’t have young kids.

“Everybody does have skin in the game,” Wiles said. “It’s just a question of how much you recognize it.”

Search and searching

When the Woolfs saw their second child care option fall through a couple of weeks ago, they briefly considered taking on a one-hour commute to secure a spot for their daughter in the next county over.

But then they got a tip about a new child care provider moving to Hays this fall and are now scheduled to send her there, pending the licensing approval process.

Until then, they’re relying on a patchwork of support from friends and family. Some days, an aunt will care for their daughter. The rest of the time, she’ll be watched by a former coworker who had to quit her job this year after being unable to find day care for her son.

But Zach Woolf said that compared to many others in northwest Kansas, his family is fortunate because it already had a network of community connections.

Any new families looking to move to towns like Hays might not be so lucky.

“If you were just dropped into Hays today to try to find a day care,” he said, “it would be incredibly stressful.”

He said it’s common for families in Hays to sit on child care waiting lists for one to two years or more, especially for an infant.

A number of his friends and coworkers have rushed to put their children’s names on waiting lists as soon as they find out they’re expecting. Woolf said that’s becoming the norm.

“If someone’s … just found out they’re pregnant,” he said, “they should really be talking about day care now.”

David Condos covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @davidcondos.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org

https://www.hppr.org/hppr-news/2021-08-19/one-familys-stressful-search-for-child-care-exposes-a-reason-rural-kansas-is-losing-people