SABETHA — It had been just a regular lesson on government in Jobi Wertenberger’s fourth grade class when Halle Renyer asked him a question that could change state history.

You see, Kansas has the sunflower as the state flower, the meadowlark as the state bird and the buffalo as the state animal, among other symbols.

What was missing, though?

Wertenberger didn’t know. But after that February 2021 lesson, he encouraged his Sabetha Elementary School students to look it up during study hall and report back to him

“Later on, I got an email from a couple of them, and they found that we don’t have a state fruit,” Wertenberger said. “In class the next day, we started looking more into it.”

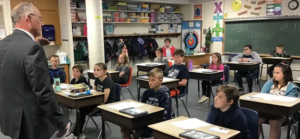

The fourth-grade teacher invited his friend, Rep. Randy Garber, and his wife to come to the class and explain that state symbols are a legislative act.

To get a state fruit, Garber explained, half of 125 representatives and half of 40 senators would have to agree to send legislation to one governor to approve or reject the recommendation.

“After that, the kids knew,” Wertenberger said. “They wanted to do this.”

Little did they know that Render’s one question would lead to an effort, spanning school years and school districts, to have 400 Kansas students write the next chapter in state symbol history.

If there’s no Kansas state fruit, then what should it be?

When the class began researching state fruits during that spring, they came to a startling realization. They’d been beaten to the (fruit) punch — someone had already tried to make the watermelon the Kansas state fruit. “They were crushed,” Wertenberger said. “I was crushed.”

But they saw a little note next to the bill on the Legislature’s website — that the bill had “Died in Committee.” The class called up Garber again, and he explained that bills sometimes just die, with or without a reason and never make it out of a committee.

The quest for a state fruit was back on, and with Wertenberger’s help, the class hosted horticulturists and arborists to go over the various native fruits in Kansas.

“We wanted something native that comes from around here, like the watermelon didn’t really come from here,” Renyer said. “It came from Florida and places that are really warm and stuff.”

Together, the class identified and voted for four native Kansas fruits that could potentially serve as a state symbol — the red mulberry, the American persimmon, the gooseberry and the sandhill plum.

One fourth-grade class in the northeast corner of the state is hardly a consensus of Kansans, though, and student Thomas Richardson asked another potentially big question in state history.

What if Sabetha Elementary asked students at other schools for their thoughts? The fruit push goes statewide

Over the summer, Wertenberger reached out to hundreds of schools around Kansas, and he got responses from 24 schools, representing more than 400 fourth- and fifth-graders.

Students at each of the schools would put their persuasive writing chops to the test by picking one of the four fruits, researching it and writing an essay trying to convince their peers to vote for it.

“We’ve had kids who have maybe struggled with other things in class, but they’ve been able to latch onto this,” Wertenberger said. “They’ve totally bought into this idea, and that’s what you love to see as a teacher.”

Paula Leidel, a teacher at Valley Falls Elementary and one of the project’s biggest and earliest supporters, said the state fruit initiative is the kind of lesson that “checks off all of the boxes in our curriculum — from government to civics to research to the writing process.”

“It’s a critical component of why we’re doing it, but it then becomes a labor of love when the kids realize what they can do and the impact they’re having,” she said.

As luck would have it, a Valley Falls Elementary student — Alucard Heinen — would win the overall contest for his essay on the sandhill plum.

Each of the winners for their respective fruits then recorded short videos reading through their essays, and on the Friday before Kansas Day 2022, the 400 students watched the videos and voted for their favorite.

Reports show the election was close, but after a neck-and-neck battle with the red mulberry, one fruit was the students’ consensus.

The sandhill plum. What is the sandhill plum?

Although they might not know it, most Kansans have probably seen a sandhill plum (also known as the sand plum, or chickasaw plum).

Nowadays, Kansas is more known for its wheat and grain crops, but in the early 20th century, the state was actually a national leader in the grape and apple industries. Prohibition and a hard freeze effectively killed off both industries, though, said Dennis Patton, a Kansas State University Research and Extension horticulture agent.

Few native fruits now are commercially grown at scale in Kansas, and that’s why Patton gave the students credit for still finding a fruit that well represents the state.

The trees on which it can be found grow in about three-fourths, maybe more, of the state’s counties, Patton said.

The sandhill plum particularly thrives in loose, well-drained sandy soil, and when Patton was a child, the fruit was a common sight along roadsides and in pastures.

“It’s a thicket-forming plant, so we’d have big brushes of them,” Patton said. “We’d go pick the plums every summer because the fruits are probably the size of a large marble, and they’re very tasty when you cook them down and make jams and jellies.”

Aerial spraying in the past few decades has tapered off the number of sandhill plum trees, but the trees are still relatively common, Patton said. It has a tart, plumlike taste, but like any other fruit, becomes sweet in a jam or jelly.

For the students, it just seemed like a natural choice. “Some of us researched it, and it turns out that it grows all around Kansas, and it makes a good jam, jelly and I think even wine,” Sabetha Elementary’s Cecelia Becker said.

“Everybody likes it, and it just tastes good,” said Tanith Montgomery, also of Sabetha.

Some of Kansas’ most cherished symbols started in its schools. The ornate box turtle became the state reptile when Caldwell sixth-graders lobbied for it in honor of the state’s 125th anniversary.

The state amphibian, the barred tiger salamander, only got its status after a second-grade class at OK Elementary in Wichita got thousands of other students across the state to join them in a letter-writing campaign in 1994.

More recently, Overland Park fourth grader Casey Friend was instrumental in getting limestone, galena, jelinite amber and the channel catfish approved as the state’s rock, mineral, gemstone and fish, respectively.

Even the state insect, the honeybee, had actually started as a project by students at Sabetha Elementary.

“As I was starting the project, a retired teacher approached me and told me, ‘We’ve done this before,'” Wertenberger said.

At the Kansas Statehouse, one section of its basement museum lists all of the state’s “officials.” Capitol Visitor Center coordinator Joe Brentano often takes crowds of children by it and through the statehouse’s historic halls.

He points out that students even helped pick the statue atop the capitol dome, Ad Astra.

“When students are learning about these symbols from an early age, it really says a lot that it’s coming from other students, and it’s not just one or two people or an interest group pushing for these symbols,” Brentano said.

The hardest part comes next. With a fruit picked, Rep. Garber in early February took the students’ consensus of sandhill plum and introduced it as HB 2644 — Designating the Sandhill plum as the official state fruit. The bill was assigned to the Committee on Federal and State Affairs, where it sat for weeks without a hearing.

But the students knew their job wasn’t done. They had seen livestreams of Statehouse hearings and they knew that bills can die in committee, with or without a reason. They also knew that the legislative process can be time-consuming, if they can even get the clock started for their bill.

“You don’t run on your time, you run on their time,” said Tinner Bachelor, Sabetha Elementary fifth-grader. So they set on their letter-writing campaign.

The students learned how to write and address letters, learning how to identify who their representatives are. That campaign, so far, has been yet another civics lesson for students on how to engage with legislators and push for a cause they believe in, said Sabetha Elementary principal Rusty Willis.

“It’s not just random letter writing,” she said. “It’s letter writing with a purpose.”

The campaign apparently worked, and now the students have a hearing with a yet-to-be-determined date, confirmed Rep. John Barker, R-Abilene and chair of the committee.

“My members are pretty excited about this,” Barker said. “We’ve done this before, with the state rock several years ago.”

Back at Sabetha Elementary, Wertenberger’s students, now students in Sheryl Plattner’s fifth-grade class, prepared for their big trip to the capitol. On Friday, the students rehearsed speeches in front of a panel of community judges, to pick the lucky few students that would get to testify to their cause in front of the House committee.

The teachers beamed with pride on all their students had accomplished. “I’ve been learning alongside these kids, but everything that’s been done, it’s them,” Wertenberger said. “I help them contact people and give them that kind of help, but it’s been their idea and their work.”

Some students speculated on what they might push for next if they’re successful with the sandhill plum. Broccoli (with cheese) could be the state vegetable, some said, giggling in their classroom corner.

But mainly, they looked forward nervously but excitedly on the prospects of the bill they helped bring to the Statehouse, as well as on how they could leave their mark on state history.

“If someone in the future — like 20 or 30 years from now — wants to do this process again, they’ll see that we have a state fruit, and they’ll look up the process of how that happened,” said fifth-grader Sutton Davis. “They’ll find out it was just a group of fourth-graders that got it started in a small town in Kansas.”

The Topeka Capital-Journal’s Andrew Bahl contributed to this story.