Jim Fulbright

Guest Writer

Thomas Hezekiah Mix was not a cowboy by birth, but in a dazzling rise to fame he became the most flamboyant and popular of all early movie cowboys. Mix was born January 6, 1880, in the northeastern Pennsylvania hamlet of Mix Run. His father, a stable master for a lumber merchant, taught his son to love horses, a quality that paid dividends for the boy who one day would set the standard for cowboys of the silver screen. Not liking the name Hezekiah, Mix took his father’s name Edwin, and though he dreamed of becoming a circus performer, his parents discouraged it when they caught him practicing knife-throwing tricks using his sister as an assistant.

With the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, Mix aspired to soldiering and enlisted, but his army unit remained stateside guarding an artillery base in Delaware. He re-enlisted in 1901, hoping to see combat action in the Boer War, but that all changed when he fell in love with Virginia schoolteacher Grace Allin, marrying her in July 1902. Mix then took leave from the Army, but never returned. He was listed as AWOL, yet not court-martialed or formally discharged.

Following their marriage, the couple moved to Guthrie, Oklahoma, where the multi-talented Mix worked varied jobs, including physical fitness teacher, pugilist instructor, and bartender. His dashing good looks and flamboyant manner won him many friends, including Oklahoma Territory Governor Thompson Ferguson who helped him be named as drum major of the Oklahoma Cavalry Band despite the fact he was not a musician.

His band travels contributed to an eventual divorce, but Mix gained valuable contacts, most notably Zack Mulhall, the Miller brothers, and Will Rogers. In 1905, he rode in Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade with several Rough Riders who had served with the President in Cuba. Years later, Hollywood publicists would muddle this event to imply Mix had been a Rough Rider himself.

Later that year, Mix was invited to work at the 101 Ranch. He knew horses and riding from his boyhood, but his “reviews” as a working cowboy were mixed. Some veteran Miller cowpunchers claimed they had to teach him to properly saddle a cow pony. One even observed that “He could get lost in an eighty-acre pasture.” The Millers paid no attention to the criticisms because Mix was hired as a showman.

When the Millers prepared for their first public rodeo in the summer of 1905, they sent Mix and other performers to appear with the Zach Mulhall show in New York. Oddly enough, he was billed as “Tom Mixco, the “Mexican horse runner,” an unlikely description that may have taught him how easily he could reinvent his life story; something done many times over his career to the consternation of biographers who still have trouble separating fact from fiction. In truth, Mix was never a Texas Ranger; had not fought in the Boxer Rebellion in China; or the Boer War; or the Spanish-American War. Neither had he been a U.S. Marshal, nor did he ride with Pancho Villa in Mexico.

His second marriage, to Kitty Jewel Perrine at the end of 1905, barely lasted a year. In 1908 he met twenty-two-year-old Olive Stokes whose family owned a ranch near Dewey, Oklahoma. They toured the Wild West Show circuit together; Mix performing as a trick rider and expert shot. In January 1909, while in Billings, Montana, he totally surprised Stokes, not by proposing, but inexplicably organizing the necessities for a wedding, evidently not thinking he needed to consult the bride-to-be. At first, Olive thought it was a joke, but then accepted, and the couple tied the knot.

Over the next two years, Mix won the National Rodeo Championship for riding and roping. He and Olive spent the winter months at her family’s ranch near Dewey, where the town appointed him “night marshal.” The connection ultimately led to the creation of Dewey’s Tom Mix Museum.

Mix’s growing reputation in Wild West performances soon gained the attention of Hollywood, and the jaunty cowboy in the big white hat landed his first role in silent films. The Selig Polyscope Company cast him in a documentary-style short film titled, Ranch Life in the Great Southwest. The movie was shot in Dewey, and included Oklahoma’s Henry Grammer in which the duo displayed their roping talents. The film launched Mix’s movie career, and for the next twenty-five years he appeared in nearly 300 films, only nine of which were “talkies.”

Olive gave birth to their daughter Ruth in 1912, and they moved to the “Bar Circle A Ranch” near Prescott, Arizona. Olive appeared in several of Mix’s silent films during that period, and over the years, 65 Mix movies were filmed at Prescott and other Arizona locations.

The family lived on the “Bar Circle A” (now a suburban Prescott housing development) until 1917, but between his travels with the 101 Wild West show and his blossoming movie career, he was not often home. Mix frequently performed opposite twenty-year-old actress Victoria Forde, and in 1917 the duo signed with the Fox Film Corporation. It was the final straw for Olive, who claimed abandonment, leading to a nasty public divorce suit. Mix and Forde were married in 1918, and four years later she gave birth to Thomasina “Tommie” Mix.

During the 1920s Mix made more than 160 escapist matinee cowboy films in which he performed his own stunts and was frequently injured. Most of his movies were simply a means of displaying action-packed stunts, trick riding, and attention-grabbing costumes. Even his intelligent, handsome horse “Tony” enjoyed celebrity status as a result of his films, especially among young movie-goers.

As it happened, Mix’s remarkable steed also came from humble beginnings. One day in 1913, a fellow actor spotted a fine-looking colt pulling a produce wagon on a Los Angeles street. He paid cash for the horse and began training it for his own, later selling it to Mix. For the next thirty-four years, “Tony” co-starred with Mix in dozens of movies and parades. Tony was so well-known to movie-goers that he became the most widely recognized horse in the world, receiving thousands of fan letters from children each week.

With or without Tony, Mix was one of the most sought-after performers of his day, yet he knew his limits as an actor. He made fun of his shortcomings by asking the directors, “Which expression do you want, number one, two, or three.” Although he sometimes left Hollywood to travel with a Wild West show or a circus, he invariably returned to the movie business. In 1929, his last year in silent pictures, Mix worked for a small studio run by Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., which later became film giant RKO Pictures. By then Mix was forty-nine and by most accounts, ready to retire. Although his voice was considered adequate for sound movies when they became the standard in 1927, he thought sound would ruin his action films and had no interest in them. Over the next two years, Mix appeared with the Sells-Floto Circus at a hefty weekly salary of $20,000, but by 1932, when he and Victoria Forde were divorced, the Great Depression, coupled with reckless spending and many ex-wives, had wiped out his savings.

Shortly after divorcing Forde, Mix married his fifth wife, Mabel Hubbard Ward. Universal Pictures approached him that year with an offer to do “talking” pictures, which included script and cast approval. Mix was broke, so he did nine pictures for Universal, but because of previous injuries while filming, he was reluctant to do more.

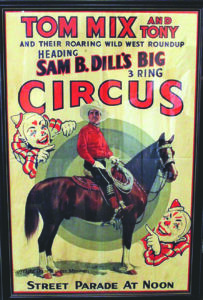

In 1933, he permitted Ralston-Purina to produce a radio series called Tom Mix Ralston Straight Shooters, a popular show from the 1930s through the early 1950s. He gave them his name but never appeared on those broadcasts, letting others do his sound work. In the meantime, Mix concentrated on the circus business. He joined the Sam B. Dill Circus in 1935, a company he later purchased. His last film, The Miracle Rider, was released in 1935, but by then, Mix wanted to stay with the circus performing with Ruth, his eldest daughter. In 1938 he went to Europe on a promotional tour, leaving Ruth behind to manage his circus. The circus failed, and Mix blamed his daughter, excluding her from his will.

On the afternoon of October 12, 1940, Mix was driving back to Southern California from New York in his 1937 Cord 812 “Phaeton.” On a lonely unpaved road near Florence, Arizona, he encountered construction barriers where a bridge had been washed away. A work crew watched as his car skidded into the gully. The impact sent an aluminum suitcase careening off the luggage rack into the back of Mix’s head, breaking his neck, and killing him instantly.

An investigation gave speeding as the cause, and while some say alcohol did not play a part, several acquaintances stated he had been drinking heavily the night before. Four days later, thousands of people attended the funeral of the man hailed as “King of the Cowboys,” at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.

For all his shortcomings, Tom Mix insisted on demonstrating strong values to his many young admirers. He didn’t smoke, drink, or curse on screen, and asked that his youthful followers abide by the motto: “Straight shooters always win, lawbreakers always lose.”

His contributions to motion pictures earned him a star on “Hollywood’s Walk of Fame,” along with boot prints, palm prints, and the hoof prints of his horse Tony at the famed Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. In 1958, Tom Mix was inducted into the Western Performers Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City.

Today, on State Route 79, seventeen miles south of Florence, Arizona, there’s a monument where Tom Mix died. It includes a bronze plaque that states: “In memory of Tom Mix whose spirit left his body on this spot and whose characterization and portrayals in life served to better fix memories of the Old West in the minds of living men.”

Tom Mix was one of several famous film stars and show people to have started their careers at the 101 Ranch. They, along with the unique history of the ranch and its people will be the focus of the “101 Ranch Western and Antique Trade Show” in Blackwell, Oklahoma on April 11 and 12. The two-day event at the Kay County Fairgrounds Livestock Center features 101 Ranch and Wild West Show artifacts as well as antiques and other Western memorabilia for viewing or sale. The show, presented by the 101 Ranch Collectors’ Association, is open to the public Friday, 12 to 5 pm, and Saturday, 9 am to 4 pm.