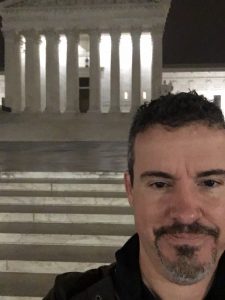

I’m not accustomed to being called a Nazi, at least not before 7 a.m. on a Monday. I was standing in front of the Supreme Court when it happened, holding a sign. My interlocutor was an administrator from the City University of New York. He held a different sign, along with the conviction that people who disagree are profoundly evil.

Later that morning, a CUNY student suggested that I was perhaps not evil, just stupid. “Intellectually unsophisticated,” was how he described me to his fellows. A professor standing nearby chimed in that I need to read Howard Zinn.

I come from a long line of Nazi fighters, I wanted to shout. I have a PhD. I’ve read thinkers on your side far weightier than Howard Zinn, and a bevy of contrary thinkers who would knock you on your ass.

I wanted them to know, in other words, that I’m really smart, and supremely righteous, and also that I’ve seen Good Will Hunting.

I’ve been thinking about how I used to put labels on people the way these people were labeling me. Some got an Evil sticker, and others got Stupid, and a good many got both. Because I’m a good person, you see. And I’ve read some stuff. We’re not just talking politics by the way—I was an omnivorous snob. Theology, marriage, childrearing, philosophy—I had firm and righteous opinions on all these subjects.

What happens over time is that life beats you up. And you either curl up into a ball of bitterness and self-delusion, or you come to recognize the limits of your wisdom and virtue. The limits of yourself.

So life will provide the education (if you’re willing to listen), but you sure can accelerate the process by reading books that open your mind and heart. That used to be what we told ourselves schools were for—to prepare our children to be good citizens, good neighbors. People, in other words, who can share space with other humans and get along without killing one another. 1

What I’m suggesting is that a good way to assess the quality of your education is the extent to which it imparts not necessarily a change of opinion, but compassion for people with other opinions.

Lately it seems like universities, and news programs, and politicians, and our social media feeds, and a thousand other more subtle influence-peddlers specialize in the opposite. They tell us good people can only believe one way, and that people who believe otherwise are bad, broken, and dangerous.

And where do you go, from there? When your enemy is a “libtard” or a Nazi? Well, to the barricades is where, because there’s no negotiating with irrational evil. We’re seeing only the beginnings of it in this country, but history paints a clear enough picture of where it ends. We keep hacking away at the roots of civil order, yet we’ll be stunned when the tree falls on our heads. Perhaps more of us are irrational than we realize, and maybe a little evil, too.

Now look, of course I have tons of solutions when it comes to reforming schools and universities and politics and churches and, most importantly, every one of you. But if I’ve learned anything, it’s that none of this matters if I am not daily about the business of reforming me. So, while I was tempted to write off these people as Marxist enemies of the liberal order, I kept in mind that no matter what they believe, they’re also humans with families and bills to pay and fear of the future and questions inside about what the purpose of all this is, what the purpose of them is.2

None of this reflection led me to put down my sign and join my opponents’ chants, but it helped me keep some charity in the face of name-calling. To speak kindly with a lady who, God bless her, wanted to have an earnest conversation about how I could possibly believe what I believe. To tell a gentleman how hilarious his ad lib responses to my side’s speechifying were. To get a selfie with a guy wearing a funny hat.

And I want to believe—though I know it may very well be just self-serving sentimentality—that my little kindnesses, once I’d gotten past some of my irritation and self-importance, made them leave feeling a little better about someone like me, too. Am I more likely to vote their way, or they mine? Of course not. But maybe our grandchildren will be less likely to pick up bricks and smash one another’s skulls in. And in this world that we’re making for ourselves, that’s no small thing, is it?

- Now educators have to market their wares as workforce preparation.

- To be clear, I’m not pretending what some of them believe doesn’t lead, if unobstructed, to mass graves. Some are indeed self-professed Marxists who despise the liberal order, and who if given power might very well swing me and my children from lampposts as an object lesson in the importance of compliance with the aims of the Revolution. But that doesn’t mean they have less humanity than me. Nor that I, under different circumstances, am too inherently virtuous to embrace similarly evil dogmas.