In earlier times, elevated political status and powerful rank did not come easily for Kansas women. Achievement was slow when women were for serving coffee rather than serving in office. Legislatures had cloak rooms for men and no rest rooms for women; women were for introduction as a spouse, not for introducing legislation. By law, women might be permitted to run for office, but by custom they were rarely allowed.

In 1974 the Republican Party refused to endorse Joan Finney as a candidate for state treasurer because she was a woman. She switched parties, ran as a Democrat and won, was reelected three times, the first woman to hold that office, and for 16 years.

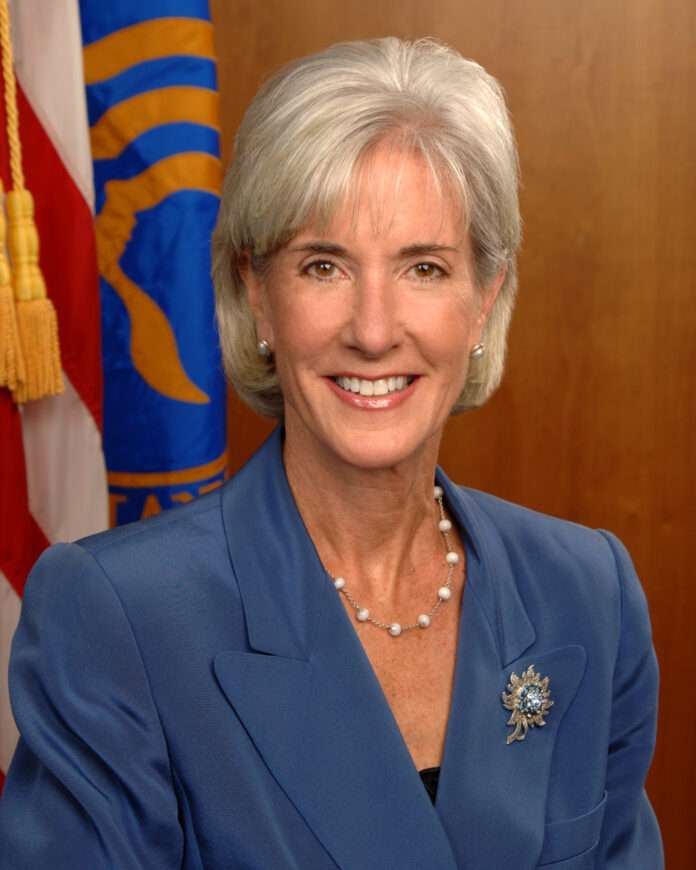

By the time Finney elbowed her way into the 1990 race for governor, other women were running and winning, among them Kathleen Sebelius; she had served successful appointments to state boards including the new Governmental Ethics Commission (1975); she was elected to four 2-year terms in the Kansas House of Representatives (1987-95), two four-year terms as Kansas Insurance Commissioner (1995-2003), and two terms as governor (2003-2009). In 2009 she became Secretary of Health and Human Services in the Obama administration.

Sebelius’s election as Insurance Commissioner was a keystone, the achievement not in challenging a male incumbent, but by challenging the legacy of corruption in that office. She promised to end the shadiness and cronyism that by 1994 had defiled the Insurance Department.

Sebelius confronted the incumbent commissioner, Ron Todd and the powerful, closed-door industry that had kept Todd and two predecessors – Frank Sullivan and Fletcher Bell – in office for half a century. Over the decades, state insurance commissioners collected most of their campaign money from the industry they were supposed to regulate, and from private lawyers rewarded with lucrative assignments to defend the state’s worker compensation or medical malpractice funds.

A commissioner had sole authority to decide who could sell insurance in Kansas and for how long, the rates they charged, and the policies they could offer, among other powers. Nearly all business was conducted privately. The industry took care of the commissioner and the commissioner took care of the industry.

The voters believed Sebelius. She won, and again in 1998, by wide margins; in 2002 Sebelius ran for governor, defeating Republican Tim Shallenburger, the House Speaker. Sebelius became the second woman, after Finney, to be elected governor in Kansas and in 2006, the first to be reelected.

*

Sebelius’s election capped a decade of rapid advancement for Kansas women in public service. In the early 1990s, women had risen to unprecedented ranks at the Kansas statehouse. They were running state agencies, heading legislative committees, leading the political parties.

Sandy Praeger, a Republican state senator from Lawrence, succeeded Sebelius as Insurance Commissioner in 2002, and was prominent among the few moderate-liberal Republicans still in state public office. Once a stable ally and solid loyalist in the party’s northeast Kansas base, she resisted the Republican lurch to the far right. Praeger became an apostate to the Tea Party base that worshiped Gov. Sam Brownback. The far right had no use for a Republican brand that once made Kansas a launch pad for national patrimony.

Prager built on Sebelius’s straight-arrow approach in managing the Insurance Department. She viewed the office as an advocate for consumers and citizens, rather than a cash sluiceway for the insurance industry. Prager also challenged GOP conservatives by endorsing many reforms in the federal Affordable Care Act. She was among the first to urge the state to expand Medicaid and establish a health care exchange to allow Kansans to shop for insurance policies. Otherwise, she said, thousands of Kansans below the poverty line would go without coverage, and with Medicaid expansion (and federal dollars) denied, dozens of rural hospitals would likely close. Brownback and the legislature ignored her.

Twenty years later, a half-dozen rural hospitals have closed and Kansas is one of a dozen states still resisting an expanded Medicaid, leaving roughly 150,000 of the state’s poor with no access to affordable health care.

Prager was elected to three 4-year terms as Insurance Commissioner, and was in public office nearly 30 years since her election to the Lawrence City Commission in 1985 ‒ all the time, a Republican. The former mayor of Lawrence ‒ at the time a vice-president of Douglas County Bank ‒ was elected to the Kansas House of Representatives in 1990, served one term, then was elected to the Kansas Senate in 1992. She was reelected in ‘96 and ‘00; in 2002, mid-point in her fourth 4-year Senate term, Prager was elected Insurance Commissioner. When her third term ended in January 2014, she left the office, politics, and the Republican party.

(Next: Elwill and Nancy)