The USDA has access to thousands more weather stations now than in the past. That, combined with 30 years of new data, led to big changes in its hardiness map of cold winter temperatures in Kansas.

Kansans may take a chance on some new plant varieties in gardens and nurseries and on farms next year after the U.S. Department of Agriculture changed its hardiness zone map.

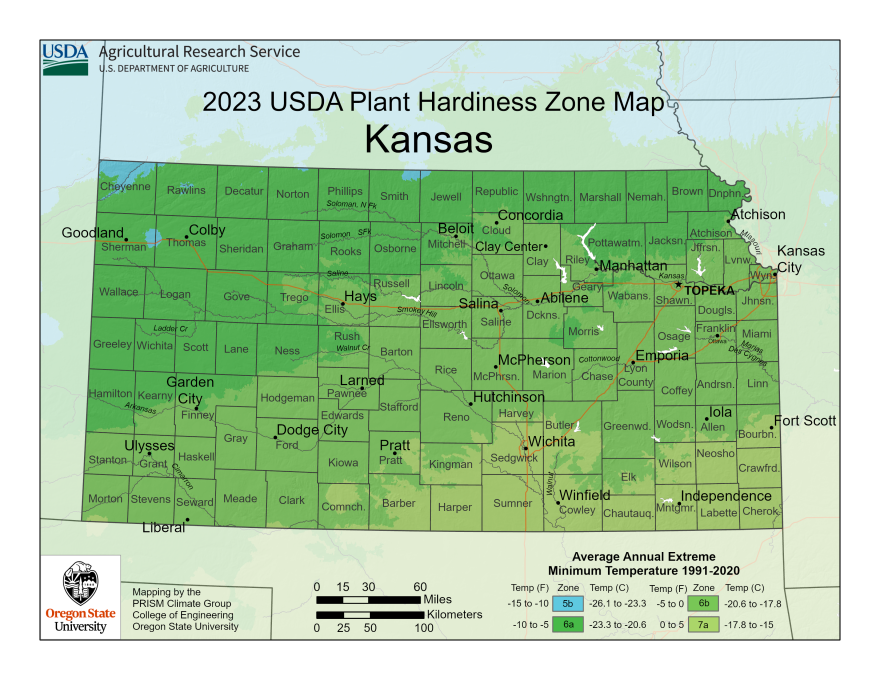

Most of Kansas has been recategorized as one half-zone warmer on the map, which the agency updated last month for the first time in 11 years.

The hardiness map reflects the coldest winter temperatures recorded annually by weather stations across the U.S.

Growers use it to pick plant varieties that should survive the bitterest nights of their local winters. The federal government uses it to set crop insurance standards.

“It’s critical,” said Cheryl Boyer, a professor at Kansas State University’s Department of Horticulture and Natural Resources. “I would say everybody involved in plant production or growth of any kind is using this map.”

Boyer also directs Kansas State Research and Extension programs related to horticulture and natural resources.

“To me, the biggest change if you’re a gardener,” she said, “is in the southern part of the state.”

Wichita, Fort Scott and surrounding areas shifted from zone 6b to zone 7a, meaning gardeners there could check out plant recommendations from northern Oklahoma for inspiration.

“That’s open season on trying some new things,” she said, “but also being OK with losing a plant if we have a really extreme winter some year.”

In other words, growers should be aware that an exceptional cold snap could still buck the USDA’s adjusted map.

Based on 30 years of data, about half of the country has shifted a half-zone warmer on the map.

However, the USDA hasn’t linked this to climate change.

It wrote in a news release that the new map partly reflects efforts to record temperatures in more locations.

Several thousand more weather stations contributed to the 2023 map – 13,412 stations compared to the 7,983 that provided data for the 2012 version.

Additionally, the agency said that the lowest winter temperatures in each area can vary significantly from year to year.

“Map developers involved in the project cautioned against attributing temperature updates made to some zones as reliable and accurate indicators of global climate change,” the agency said in its release, adding that studying climate trends usually requires longer-term data.

Other groups, such as the nonprofit Climate Central, say the changing growing zones fit a trend of global warming caused by carbon pollution in the atmosphere.

If the trend continues, Climate Central says, this could expand the range for high-value crops such as oranges, but it could also allow some crop pests to spread north.

Celia Llopis-Jepsen is the environment reporter for the Kansas News Service. You can follow her on Twitter @celia_LJ or email her at celia (at) kcur (dot) org.