By Duane Schrag

Special to the Rural Messenger

When word that House Bill 2273 had been introduced in the Energy, Utilities and Telecommunications committee last month, it took some people by surprise. News arrived by the grapevine.

“We got word that it had been filed late Wednesday evening when (the Kansas Healthcare Collaborative) notified our county health officer on a routine matter,” said Reno County Counselor Joe O’Sullivan. “The time limit to submit written testimony was Friday at noon.”

The bill was of particular interest to Reno County residents. NextEra Energy, a Florida-based company that bills itself as the world’s largest developer of renewable energy, was poised to apply for a conditional use permit to build a wind farm in southeast Reno County.

News of the plans had ignited a firestorm of protest from citizens in that part of the county. For weeks during the final months of 2018 they packed county commission meetings to voice their objections.

And now, seemingly out of the blue, a bill materialized in the House energy committee that was, in O’Sullivan’s words, “designed for one thing, and that is to shut down wind energy.”

The chairman of the committee is Rep. Joe Siewert, who lives in southern Reno County (see related story).

What followed over the next few days amounted to a hastily staged skirmish over wind development in Kansas. The committee took testimony supporting the bill the following Tuesday (Feb. 19); it heard from opponents on Thursday.

By Friday, the bill was dead.

It seems unlikely, however, that the war over how to situate wind farms in Kansas is over. Many of the claims made by both sides don’t hold up under scrutiny. And with mounting evidence of the profound disruptions caused by climate change, it’s virtually certain that pressure to bend the arc of energy production away from carbon-based fuels will only grow.

* * *

While there were expansive disagreements over the merits of the bill, there seemed to be no disagreement on one central point: the bill, if enacted, would make sweeping changes.

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the bill was that it would have established setbacks – the minimum distance from the turbine to the nearest home or public building – of a mile and a half. Typically, setbacks are roughly a quarter mile; the setbacks for the proposed Pretty Prairie Wind Farm in Reno County are 2,000 ft. or just over one-third of a mile.

Several representatives of the wind industry said the setbacks were so onerous they would effectively kill wind development in Kansas. A spokesman for NextEra testified that none of the seven wind farms developed by NextEra in Kansas would have been built if setbacks of 1.5 miles were required.

Half the counties in Kansas have no zoning regulations, and supporters of the bill claimed that this made them easy prey for wind developers.

The wind industry countered that even in unzoned counties, county commissioners can block wind projects that don’t meet their approval. A wind industry lobbyist cited agreements for decommissioning (removal of turbines when they are no longer used), road maintenance and payments in lieu of taxes.

“So those three agreements are the opportunity for the county – in an unzoned county – to have final approval authority over whether a wind farm is actually going to come into a community,” lobbyist Kimberly Gencur Svaty testified. “If the county doesn’t sign off on either one of those three agreements, even though the county is not zoned, the wind project will not move forward.”

But Svaty said after the meeting that there is no state law granting counties authority to block wind farms if developers don’t sign one of those agreements.

The Kansas Supreme Court has upheld the right of counties to declare a moratorium on wind farms.

Sedgwick, Wabaunsee and McPherson counties have moratoriums in place, and Reno, Marion and Nemaha counties have all discussed them.

Perhaps the most dramatic testimony against HB 2273 came from Alan Anderson, an attorney with Polsinelli, a law firm with offices across the United States. His written testimony bristled with a long list of the bill’s shortcomings. It would purportedly violate the Kansas Constitution, the County Home Rule Act, and the Kansas Zoning Enabling Act.

On top of that, it implicates the state and federal constitutions, “it tramples on the goals of essential due process protections for landowners and their property rights”, violates the freedom of contract, creates regulatory uncertainty, harms the state’s ability to compete in business, substitutes local experience and expertise for bureaucratic fiat (he probably meant the opposite), and is so vague as to be unworkable.

This landslide of imperiling legislation seemed to overwhelm at least some committee members.

“My basic problem is the constitutional aspect of this,” said Rep. Anne Kuether, ranking minority member. “I just can’t go along with this. I think the whole bill is just basically flawed. This is clearly questionable on constitutionality.”

That’s not the take of Prof. Richard Levy, who teaches constitutional law at the University of Kansas Law School. He reviewed Anderson’s written testimony from a legal perspective, noting that he takes no position on the bill’s merits as policy.

“The legislature is free to change county home rule or city zoning authority,” Levy said. “The arguments… really misunderstand the authority of cities and counties, which is always going to be subordinate to the authority of the state. I don’t mean to be saying that there are no constitutional issued raised, just that the issues concerning home rule authority or zoning power of cities and counties are policy issues, not constitutional issues.”

He was skeptical too about the claim that the bill would trample due process protections. The bill is an example of the state trying to balance one group’s rights with those of another.

“Since the early 20th century it’s been pretty much established that it doesn’t violate due process for the state to make judgment calls about competing uses of property,” he said.

What about taking away the freedom to make contracts?

“That is an argument that has not prevailed since 1936,” Levy observed. “It would be a breakthrough to win that argument.”

And it being too vague? Good luck with that — nothing is truly black and white.

“It is really, really, really easy to make a vagueness argument, and they are made all the time,” Levy said. “It’s almost impossible to write a law that has no gray areas. The bar for winning a vagueness argument is very high.”

One aspect of the bill that elicited considerable comment was the requirement that the red warning lights on towers be turned on only when planes are nearby. So-called Aircraft Detection Lighting Systems (ADLS) have been approved by the Federal Aviation Administration for several years, but the technology is not widely used.

The bill, as introduced, would have required that towers built after the law goes into effect would have to use ADLS technology.

Several opponents of the bill argued that this was attempting to usurp the authority of the FAA. Indeed, when asked about the FAA’s position, a spokesman said that the FAA allows the lighting in some, but not all, circumstances.

Mandates for the lighting are spreading. North Dakota has passed legislation requiring ADLS technology; a bill requiring ADLS on wind towers passed both houses of the South Dakota legislature in early March without a single dissenting vote, and in Minnesota a bill is being considered that requires ADLS on not only new towers, but on existing towers also.

Following the testimony, several amendments were offered to address the concerns raised. One amendment reduced setbacks from 1.5 miles to just over a half-mile. Another exempted all counties with zoning – the setbacks would apply only in counties without zoning. Another modified the language on the lighting to acknowledge that the FAA’s decisions are final with regard to lighting.

Two votes were taken to get the bill out of committee and onto the House floor. Both failed.

(Next week: Property values, gag orders, health risks…)

*

Seiwert says HB 2273 “is not my bill…”

TOPEKA – As he stood to address his House committee, Rep. Joe Seiwert struggled to maintain his composure. He had a written statement but faltered as he read, his hands shaking as he added the document to the testimony for House Bill 2273.

“This is for the record,” said the chairman of the House Energy, Utilities and Telecommunications committee. It was a phrase Seiwert used four times in the course of making his brief announcement. Someone – he didn’t name names – had sent emails to committee members suggesting Seiwert orchestrated the bill for personal reasons.

“This bill was not drafted at my request and it was not introduced to affect my property or gain any sort of advantage,” the statement says.

Officially, the bill was introduced at the request of committee member Randy Garber, who is from Sabetha, where there was fierce opposition to a wind farm NextEra is considering in Nemaha County.

Seiwert made his statement at the end of the Statehouse hearing on Feb. 21, which was devoted to testimony against the bill. Before delivering it, he polled staff from the Revisor of Statutes and Legislative Research offices, asking them whether he had a hand in drafting the bill.

They all said no.

“It is not my bill and never has been my bill,” Seiwert said. “I had no input whatsoever with any of the drafters of the bill. I referred them to the Revisor’s office. I had calls back home to people in my district that said that I was the drafter of this bill. That is false. I want that on the record.”

An assistant in Seiwert’s office declined to provide the emails.

“I have been the chair eight years.,” Seiwert told the committee. “I’ve been in office 11. There were some emails sent out by lobby groups and I report here for the record. And I have copies of the emails that were sent by a college professor to everybody on this committee. I have the copies and everything, so there’s no question that my involvement was charged, that I was the main drafter of this bill.

“For the record, one of my favorite phrases in the Legislature is, ‘Your word is all you really have here.’ We serve in an arena where trust and integrity are the things that allow us to work together to get things done. I take that very seriously. That’s why I am talking here. I allowed H B 2273 to have a hearing to be worked, because I believe part of our job is to consider ideas, even ones we might disagree about.”

In a later interview, Seiwert said he has taken steps to report the incident.

“I filed a complaint about the lobbying tactics of the lobbyist who gave misleading information to the county and to the chamber of commerce,” he said. “Technically could result in them losing their lobbying license.”

At the hearing, Seiwert apologized for becoming emotional.

About the Pretty Prairie Project:

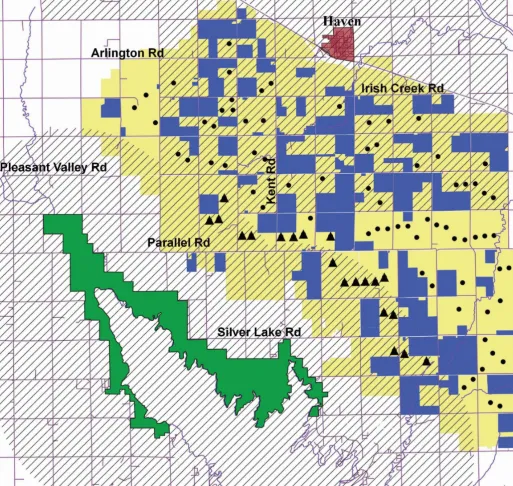

– The proposed Pretty Prairie Wind Farm is expected to consist of more than 80 wind turbines; the developer, NextEra Energy, asked the Federal Aviation Administration to evaluate 91 turbine sites to ensure they are not a hazard to aircraft.

– NextEra has said the turbines will be capable of generating 220 MW when operating at maximum capacity. One megawatt – or 1 million watts – if generated continuously can power 840 homes. Historically, Kansas wind farms generate about 40 percent of their rated capacity (because the wind doesn’t blow continuously). Based on that, the wind farm would produce enough to electricity to power 75,000 households.

– Last year, a Boston-based company, Iron Mountain, announced that it signed a 15-year power purchase agreement with NextEra to take 145 MW of electricity from the Pretty Prairie Wind Farm. A spokesman for NextEra said it has also signed a power agreement with Home Depot for 15 MW.

– The current cost of fuel required to generate the wind farm’s annual power output is about $700,000.

– In Kansas, wind farms are exempt from property taxes for 10 years. Based on industry estimates of wind farm construction costs (NextEra declined to say how much it will spend building the wind farm), NextEra will save approximately $56 million in property taxes during that period.

Before the Reno County Planning Commission makes its recommendation to the county commission regarding the Pretty Prairie Wind Farm it will conduct a public hearing that opens at 3 p.m. April 4, in the Atrium Hotel and Convention Center, 1400 N. Lorraine, in Hutchinson.

Attendees will be given 5 minutes each to speak.

You may also submit your comments in writing. They must be received before the planning commission closes the hearing.

Comments by email are preferred, and may be sent to: [email protected]. There are no special requirements for the Subject line, but suggested subjects are “Case #2019-01” or “Pretty Prairie Wind Farm.”

Comments submitted by letter or postcard should be addressed to: Reno County Public Works Department, 600 Scott Blvd., South Hutchinson, KS 67505.

Following the public hearing, the planning commission will decide whether to recommend approving a conditional use permit, and what conditions to impose. Here are some possible requirements:

- Tax offsets – state law grants new wind farms a property tax exemption for 10 years. NextEra won’t say how much the wind farm will cost, but it likely will be more than $300 million. A state exemption would forgive about $56 million in local property taxes that support local entities such as the county, local school district, township and community college. The county could require that NextEra pay some or all of that amount.

- Decommissioning – removing wind turbines no longer in use will cost upwards of $100,000 each, perhaps more. In some instances, wind farm developers are required to deposit an amount – $5,000 per year per turbine, for example – into an escrow account to ensure that money is available.

- Setbacks – county regulations now require that turbines be no less than 1,000 feet from residences; the developer has agreed to double that distance. The developer also promises to abide by the setback even in unzoned areas. It is unlikely the county will demand that distance be increased even further.

- Shadow flicker – some locations restrict the maximum time any residence may be in the shadow of turbine blades. Typically, the moving shadow from the blades of any one turbine would fall on a home for less than an hour and half a day.

- Transparency – the county could insist on verification that NextEra contracts do not discourage landowners from sharing information about their experience.